A common question I get about the Pacific Crest Trail revolves around navigation. "How easy is it to find your way?" or "Is the trail well marked?" are often curiosities to people who haven't hiked the trail before. This post will help explain the nature of the PCT and how to find your way from Mexico to Canada.

First of all, the PCT is a very well-trod footpath. It has been a proposed trail since the 1930s, designated as a National Scenic Trail in 1968, and finally fully completed in 1993. Since then, hundreds of hikers every year set out to walk the entire 2,650 miles along a trail that is merely one foot wide.

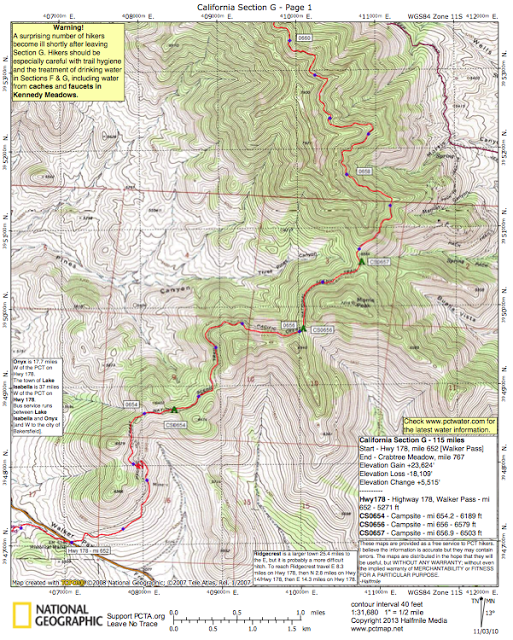

MAPS

To find your way through three states and from one end of the country to another, hikers navigate in a few different ways. Most carry detailed, printed topographical maps that cover the entire trail in something like 500 pages worth of data. (You can see the maps yourself here). A hiker named Halfmile has very generously devoted his time and effort to make these maps available online for hikers for free. Not only do they show the PCT's route over contour lines and county lines, but they highlight campsites, water sources, show warnings and regulations, and give helpful tips for each section. For almost every thru-hiker on trail, these maps are a lifeline and a God-send. We divide up the pages by section and at each resupply stop we mail ourselves a new section of maps so we don't have to carry the entire 500 pages at one time. A lot of hikers re-use the maps by writing their journal entries on them.

Besides printed maps, hikers these days have become more and more reliant upon iPhone apps and guides to help them along their journey. The two most prevalent sources of electronic information this year on trail were Halfmile's App and Guthook's PCT Guide. (You can read more in detail about these programs on my "staying wired on trail" blog post here).

Both of these apps were helpful in their own way. Halfmile's App worked in conjunction with his printed maps; they showed waypoints, points of interest, campsites, and let you know exactly which mile marker you were at (and how many miles to the next waypoint). If you happened to stray off the trail, the app told you how far you were away from it and gave you a compass direction to find your way back.

Guthook's App had several helpful references that Halfmile did not: it utilized GPS tracking (which worked even without cell service) to pin-point your location on a map of the PCT. It gave you detailed information and photos of upcoming campsites, road crossings, water sources, and towns. It also gave you accurate elevation profile data, so you could see your overall gain/loss for the day and gauge your hiking speed accordingly. You could also see your approximate mileage based on nearby waypoints, but unlike Halfmile's App, it did not give an exact mileage number of your current location.

Both apps had their pros and cons, and by utilizing both on trail, the data was infinitely more useful. (For example, Guthook often had campsites listed that Halfmile did not, and Halfmile often had more detailed town information that Guthook did not). Overall I was very impressed by the ease of use and helpfulness of both these apps. On more than one occasion I found myself off trail, and with a quick look at Guthook's GPS, I could easily navigate my way correctly back.

On my hike, I relied most heavily on the PCT apps I had on my phone, and Katie relied on the printed maps. With both sets of information, we were able to get an overall view of what our hike looked like. You can get away with one or the other, but having both is invaluable.

I grew so attached to knowing my exact mileage and elevation for each day, that when I returned home and went on a long dayhike, I found myself reaching for my phone on more than one occasion to check my mileage. It was annoying realizing that I didn't have information close at hand anymore!

NOTES and MARKERS

If you set out to hike the PCT with a set of maps and good head on your shoulders, you will easily find your way to Canada (provided you can read the maps accurately, of course.) Although this is enough to guide you, once you're on trail you quickly discover that the PCT has some tricks up its sleeve. The footpath is simple enough to follow: generally its the only trail there is to follow, but just in case you're worried, every few miles or so you come across a PCT marker to reinforce that you are, in fact, on the correct trail.

But sometimes, especially in popular wilderness areas and national parks, you come across a multitude of trails all converging in the same place. There are signs everywhere, and more often than not, the PCT is not explicitly marked. The trail junction will say something ambivalent like, "to Spruce Glade Trail" or "to Bear Ridge," and unless you happen to know the surrounding system of trails really well (and you won't) you have no idea which path to choose.

Despite that the PCT signage people have some work to do in this area, most of the time you won't have to take out your maps to puzzle over which route to take. Why not? Because there have been hundreds of hikers who have had this same exact problem hundreds of times before you. And because hikers are naturally helpful, generous people, they will have left you a clue, just so you don't make the same mistakes they did.

These clues come in several different forms.

First:

Vandalization.

It's probably not kosher, but the simplest way to inform hikers where the PCT goes is for the first hiker to write on an existing sign in sharpie: "PCT North" with an arrow. And unless the sign has been swapped out recently by the forest service, these signs stick around for a long time, so years and years of hikers can all follow the same sharpie note that someone wrote back in 1998. And inevitably, a few minutes later you will see that distinctive PCT sign nailed to a tree or post, confirming your choice.

Second:

Notes on trail.

If there's not a good sign to write on, hikers resort to writing on little scraps of paper and leaving them behind with duct tape or under a rock. These sorts of notes are found all over the trail for various reasons: trail markers, wayfinding, pointing the way to water, warning hikers about wildlife in the area (bears, wasps, etc), and anything else you want to explain to those behind you. Some hikers even leave little notes of "hello! I miss you!" to hiking partners they haven't seen in a few days. These notes are extremely useful, joyful, and an efficient way to pass back information to a group of people who have no access to cell phone service or social media. In some ways, the PCT is its own pony express, creating communication in a place where otherwise there could be none.

Third:

Markers in the dirt.

If there's not a good sign to write on, or any paper to write with, the simplest way to tell a hiker where to go is to draw in the dirt. You can create all kinds of leave-no-trace artwork with sticks, rocks, pinecones, leaves, or lines in the sand. These creations are semi-permanent and easy to follow. We often come across mileage markers ("100 miles!" "2000 miles!") created on trail with bits of rocks or pinecones. But more importantly for navigation, we leave each other arrows, "this way!", or just two deeply dug tracks in the dirt that create a "highway" to walk along. If the trail split three ways, I learned to automatically look down at the dirt and search for the two parallel lines that someone created by dragging their trekking poles through the dust. These lines created a path that pointed the correct trail to follow.

In the beginning, I didn't always trust these lines or markers in the dirt. Who was to say that a thru-hiker made them? Or that they didn't lead somewhere incorrect? The markers were often vague or half-destroyed, and I usually double-checked my maps to verify the route. But in the end, the markers were always right. They were always right because hundreds of people followed those same markers every day, and if they were wrong, someone would have changed them already. Thru-hikers are very good about leaving notes for each other, as we've already discussed, and if someone had written an incorrect note, it would very shortly be changed/ added to/ corrected by someone else. By the end of my hike, I was 100% trusting every single marker I came across on trail without even a flicker of doubt, and they never steered me wrong.

FOOTPRINTS

And finally, the third way hikers navigate on the PCT is by footprints.

This is an acquired super-hero power that you gain after hundreds of miles of walking the same way. When you begin your journey, you walk for 700 miles through the most desolate desert terrain you have ever seen. In fact, it is so desolate that no one except thru-hikers ever seem to walk these trails. Thru-hikers, after all, are the only ones stupid enough to walk in the desert for two months.

But after days and weeks and months of walking the same pace, behind the same exact hikers every day, staring at the trail all day, one foot in front of the other, you start to notice things. Weird things. Like footprints. Sure, there are hundreds of them, daily tramping over each other, burying the old ones beneath the new prints, but somehow... they are familiar.

You start to notice the differences. You start to notice the patterns, and the lugs printed into the dirt, and the traction marks. You notice the backwards brand names, the size of the print, whether they pronate or supinate. At breaks you start to notice what shoes your fellow hikers are wearing. You find yourself glancing at their sole patterns when they sit down. You start noticing these patterns showing up in the dirt ahead of you while you're walking all day. You notice which shoe prints show up the most often. (Brooks Cascadias.)

And then, one day, the magic super-hero power strikes you. You can see them, the hikers, in the dirt. You know exactly who left each print. You know exactly when they came through, and who hiked through after them. You know exactly which direction they took, which path they chose, which water source they stopped at. And like a forest native, you begin to track them. You make choices based on their choices. Did they go to the left or right? Did they take a lunch break under this tree? Did they take the side trail to town or keep going?

Sometimes these choices influence your own. My hiking friends Wocka and Giddyup found their way to Kennedy Meadows one day because they followed Katie and my footsteps through the dirt. When our footprints suddenly ran out, they realized we had turned onto the paved road to the right of the trail and walked to town instead of continuing on the PCT.

When Katie and I walked through the Mojave Desert Aqueduct at night, we had a difficult time navigating the trail in the dark, since it was so flat and open. To keep ourselves on track, we shone our headlamps on the trail and followed Sansei's distinctive Chaco footprints all the way to our next water source.

When our friend Birddog took afternoon naps, he would wake up to find himself disoriented and often began hiking accidentally southbound, until he ran into another hiker. Finally Rotisserie gave him the tip: "when you wake up from your nap, Birddog, just check which direction the footprints are going!"

When Katie and I wore the same Brooks brand trail runners, I would hike behind her, intentionally placing my left footprints beside her right footprints as I walked. Hikers behind us would frequently joke, "it looked like you were hopping down the trail!"

We became stealthy, knowledgeable trackers and learned the footprints of our friends as well as we knew their habits and personalities.

And so, through map and GPS use, markers, notes, and footprints, these are the resources PCT hikers utilize to guide themselves - and each other - north from Mexico to Canada.